Thieves use stolen personal data to get treatment, drugs, medical equipment

By WSJ- STEPHANIE ARMOUR- Updated Aug. 7, 2015 7:08 p.m. ET

Kathleen Meiners was puzzled when a note arrived last year thanking her son Bill for visiting Centerpoint Medical Center in Independence, Mo. Soon, bills arrived from the hospital for a leg-injury treatment.

But her son had never been there. Someone had stolen Bill Meiners’s Social Security and medical-identification numbers, using them to get care in his name. If he had been injured, she would have known: Mr. Meiners, a 39-year-old convenience-store worker with Down syndrome, lives with his parents in south Kansas City.

To clear things up, Mrs. Meiners, who turns 74 on Saturday, took him to the hospital to show he was fine. It didn’t work: She says she spent months fighting collection notices and trying to fix his medical records.

In a twist on identity theft, crooks are using personal data stolen from millions of Americans to get health care, prescriptions and medical equipment.

Victims sometimes only find out when they get a bill or a call from a debt collector. They can wind up with the thief’s health data folded into their own medical charts. A patient’s record may show she has diabetes when she doesn’t, say, or list a blood type that isn’t hers—errors that can lead to dangerous diagnoses or treatments.

Adding insult to injury, a victim often can’t fully examine his own records because the thief’s health data, now folded into his, are protected by medical- privacy laws. And hospitals sometimes continue to hound victims for payments they didn’t incur.

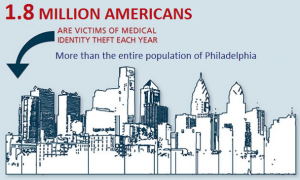

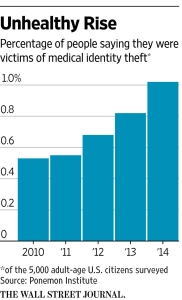

Fueling medical identity theft is the surge in electronic medical records and data breaches at insurers and health-care providers. Medical identity theft—in which someone fraudulently uses data to bill for medical services—affected 2.3 million adult patients in 2014 versus 1.4 million in 2009, according to a survey published in February by the Ponemon Institute LLC, a research concern.

Such identity theft has led about 40 companies, including Blue Cross Blue Shield Association and Aetna Inc., to form the Medical Identity Fraud Alliance. Some hospitals have turned to biometric screening to confirm patient identities.

“Criminals still go after retail and banks,” says Ann Patterson, the alliance’s program director, “but the shift is into health care.”

Federal agencies such as the Department of Health and Human Services, Justice Department and Federal Bureau of Investigation are stepping up joint investigations. “Data breaches are increasing and becoming more common,” says Dr. Shantanu Agrawal, director of the Center for Program Integrity at the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. “You can end up with diagnoses being placed in your file without your knowledge.”

And the medical establishment often doesn’t make it easy to clean up the mess, as Mrs. Meiners found out.

She began early last year with a call to the Centerpoint medical center, which she says promised to clear the fraudulently billed January 2014

leg-injury treatment. But in November, the center’s radiologists turned her son’s case over to collections, seeking $25. This year, the emergency-room physicians sent a bill for $462. And the hospital, she says, wanted her to pay a bill of about $300.

Another concern for Mrs. Meiners was that the thief’s medical information got into her son’s health records, including a

Bill Meiners last year was billed for a leg-injury treatment he never had after someone stole his Social Security and medical-identification numbers, using them to get care in his name. drug allergy her son didn’t have. She contacted her son’s insurer, which told her it removed the false information.

She says Centerpoint told her that medical-privacy laws prevent her from looking at everything in her son’s medical record because it contained the thief’s health information. Federal medical-privacy laws bar a person’s access to someone else’s data, even if the information is in their own files, medical experts say.

After the Journal requested comment from Centerpoint, Mrs. Meiners said, the hospital told her the charges were being waived.

Five Things to Know About Medical ID Theft and How to Prevent It (http://blogs.wsj.com/briefly/2015/08/07/5-things-medical-identity-theft-and-how-to-avoid-it/)

A Centerpoint spokeswoman says the hospital “urged the family to report this to authorities to investigate as medical identity theft and file a police report, and we canceled the victim’s hospital bill.” She says the hospital contacted the independent physician practices and notified the insurance company, and cleared up Mr. Meiners’s medical record so it only reflects the appropriate health information.

Mrs. Meiners says she never found out how her son’s identification was stolen. “It floors me what happened.”

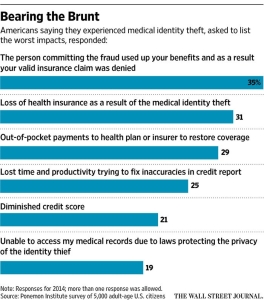

Unlike in financial identity theft, health identity-theft victims can remain on the hook for payment because there is no health-care equivalent of the Fair Credit Reporting Act, which limits consumers’ monetary losses if someone uses their credit information.

Medical identity fraud is typically resolved case-by-case. Sometimes the health plan or health-care providers absorb the losses, and sometimes they push the consumer to pay. It is often up to consumers to prove they were victims and to pursue legal remedies to erase bogus charges and debts, according to identity-theft experts.

“You can be stuck with a medical bill for services you didn’t receive,” says Ms. Patterson of the Medical Identity Fraud Alliance.

The Ponemon survey found 65% of victims reported they spent an average of $13,500 to restore credit, pay health-care providers for fraudulent claims and correct inaccuracies in their health records. “Most people are not fully cognizant of medical identity theft, which is much more insidious than financial identity theft,” says Larry Ponemon, the institute’s founder. “The effects can linger much longer.”

Thieves use many ways to acquire numbers for Social Security, private insurance, Medicare and Medicaid. Some are stolen in data breaches and sold on the black market. Such data are especially valuable, sometimes selling for about $50 compared with $6 or $7 for a credit-card number, law-enforcement officials estimate. A big reason is that medical-identification information can’t be quickly canceled like credit cards.

An undocumented immigrant, Amira Avendano-Hernandez, of Clinton, Wis., was sentenced in 2013 in U.S. District Court for the Western District of Wisconsin to six months in prison and restitution of more than $200,000 after she got medical treatment, including a liver transplant, using someone else’s name. She had bought a stolen Social Security number from a third party, according to the U.S. attorney’s office for the district. Her lawyer declines to comment.

Redspin Inc., a security-assessment firm, said in a February report that computer-data breaches of personal health information affected more than 40 million patients from 2009 through 2014, and the 164 breaches in 2014 represent a 25% increase over 2013.

Once identity information is stolen, thieves can get all sorts of health care. In 2009, Jose Amid Juarbe pleaded guilty in Lehigh County, Pa., court to identity theft to get penis enlargements for himself and a friend, according to police and court records. Mr. Juarbe declines to comment.

A retired Florida woman whose insurance information was swiped got a hospital bill for an amputated foot, even though she still had both feet, according to a report on medical-fraud cases by the Center for Democracy and Technology.

Sometimes, health-care providers are the perpetrators. Federal prosecutors charged Dr. Kenneth Johnson with using Manor Medical Imaging, a Glendale, Calif., clinic, to write prescriptions for drugs and then sell them on the black market.

Medicaid recipient Vardanush Kirakosyan, an Armenian immigrant, testified she lost her driver’s license and Medicaid card. Using her information, Dr. Johnson’s clinic ordered two antipsychotic drugs to treat postpartum depression, according to the testimony. Ms. Kirakosyan, then 43, testified she had never met the doctor, seen the clinic, taken antipsychotic drugs nor suffered from postpartum depression.

The U.S. District Court for the Central District of California in February 2014 found Dr. Johnson and colleagues guilty of health-care fraud conspiracy and other charges. Prosecutors say the clinic, outfitted with ultrasound machines and other medical trappings, was a scheme to defraud Medicare and the state’s Medicaid program by stealing or using victims’ medical identities. The clinic offered cursory or fake exams, at times busing in patients from senior centers, as a ruse to get their personal data and worked with pharmacies, according to prosecutors. The clinic offered some people money or meals to get them to provide their information.

Benjamin Barron, an assistant U.S. attorney in the district, says one victim found out about the scam when he was unable to get his legitimate prescriptions filled. “His entire medical benefits were looted,” Mr. Barron says.

Manor Medical is no longer in business. Dr. Johnson, who pleaded not guilty, is awaiting sentencing. His lawyer declines to comment. Ms. Kirakosyan declines to comment, citing her poor English.

Hospitals are setting up special investigative units to catch medical identity fraud. BayCare Health System, which has hospitals in Florida, is one of hundreds of hospitals that give patients the option to register by scanning veins in the palm. The image is converted into a number that correlates with the patient’s medical record, according to its website, to which BayCare directed a reporter.

Atlantic Health System Inc. of Morristown, N.J., encrypts patients’ records and has installed firewalls, spam filters and palm-detection security. The hospital system also requires photo identification at the time a patient registers and runs annual mandatory training for employees that includes security issues.

“Medical identity theft is a big issue,” says Linda Reed, Atlantic’s chief information officer. “They steal your medical identity and have a procedure or treatment done, and it’s fused with your records.” She says Atlantic’s systems have stopped cases involving people using family members’ insurance cards to seek treatment.

President Obama signed a bill in April including provisions aimed at helping prevent medical identity theft.

Changes are also afoot in federal health programs. President Barack Obama signed a bill in April that requires HHS to issue Medicare cards that don’t display, code or embed Social Security numbers. The action came on the heels of a hack into the database of insurer Anthem Inc. that contained personal information for about 80 million current and former customers and employees.

“Identity theft is pervasive throughout health care,” says Gary Cantrell, deputy inspector general for investigations at HHS’s Office of Inspector General. “We see it as a growing concern.”

Shaneé Halberd, 42, a special-education teacher in Kennesaw, Ga., turned to ID Experts, a Portland, Ore., data-security concern, to set the record straight after seeing a collection item when checking her credit report. It was from WellStar Cobb Hospital in nearby Austell in 2011.

Ms. Halberd made some calls and discovered someone had used her Social Security number to get treatment. She says the collection agency told her that health-privacy laws mean she can’t find out what treatment the person received. She said the bill has been waived. WellStar declines to comment.

“I was concerned their information would be commingled with mine. If that happens, it can be the difference between life and death,” she says. “It was very scary.”

Some victims say the problems from medical identity theft haunted them for years. Anndorie Cromar, now a 36-year-old medical-lab supervisor in Salt Lake City, says Utah’s child-protective services called her in 2006 to say her newborn had tested positive for methamphetamine at Alta View Hospital in Sandy, Utah.

Ms. Cromar hadn’t given birth then. Someone had stolen her identification, gone into labor, delivered a baby girl and left the infant at the hospital. The case grabbed headlines at the time, but few knew the ordeal took years to straighten out.

She says she was never able to fully settle the hospital bill the thief had racked up and eventually charged it off when she filed for bankruptcy for unrelated reasons. For months, she continued to get appointment reminders for the baby. She wasn’t able to view her own full medical records because they now contained the thief’s health information. She says she also had to go to court to get her name taken off the baby’s birth certificate.

An Alta View spokesman declines to comment, saying the hospital didn’t have an updated privacy form signed by Ms. Cromar. The Utah Division of Child and Family Services declines to comment.

“To this day, I don’t know if my name is in the baby’s medical record,” Ms. Cromar says. “It’s insidious.”

Write to Stephanie Armour at [email protected]