Bloomberg View-AUG 8, 2016 4:44 PM EDT By Megan McArdle

Last week, I outlined eight possible futures for Obamacare. By curious coincidence, few of them looked like the paradise of lower premiums and better care that the law’s supporters had promised. In the best case scenarios, they looked more like what critics had warned about — “Medicaid for all,” or fiscal disaster, or a slow-motion implosion of much of the market for private insurance as premiums soared and healthy middle-class people dropped out.

What I did not explore was why we seem to have come to this pass — which is to say, why insurers seem suddenly so leery of the exchanges and why premiums are going up so much for Obamacare policies. No one really seems to know exactly why insurers are having so much trouble in the exchanges. Insurers may know, but they have generally issued vague statements about “worse than expected experience.” The closest we’ve gotten to an assessment was a statement from a big insurer last year to the effect that people who were signing up outside of the normal enrollment period seemed to have higher-than-expected bills, while paying fewer than expected premiums. Which tells us something, but doesn’t necessarily explain double-digit premium increases.

This weekend brought a new suggestion across my desk. At Forbes, Bruce Japsen writes that insurers think providers are funding nonprofits to pay Obamacare premiums for high-cost Medicaid patients, thus sticking insurers with a lot of big bills for a lot of very sick patients.

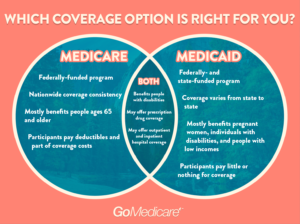

Why would they do this, you may be asking yourself? Because Medicaid reimbursements are extremely low. If you have a patient who is consuming tens of thousands of dollars a year worth of care, reimbursed at the rock-bottom rates that Medicaid permits, then it may well make financial sense for you to pay the premiums to switch that patient onto private insurance, where your services will be reimbursed at much higher rates. Since insurers are no longer allowed to charge sick people more for insurance, the insurers have to take them — and then pay their enormous bills. And since, needless to say, this only makes financial sense for patients who are extremely sick, that will have the effect of skewing the Obamacare risk pool in a very expensive direction.

So which is it, you may ask? Patients gaming the rules, or providers doing it? My answer is … probably both. Obamacare was conceived and enacted as an extremely complicated system, a sort of Rube Goldberg machine for taking in premiums and government subsidies, and spitting out something that could be called universal coverage at the other end. Literally no one I ever interviewed — except, briefly, people on the political teams in charge of passing Obamacare — said that this was a very good system. Even its savvier defenders simply said, a little ruefully, that this incredibly complicated structure was what could be passed while meeting a bunch of politically vital goals, including keeping the headline cost of the bill below a trillion dollars over 10 years, and not alienating any important interest group.

One of the major complaints about the system before Obamacare was the huge variety of overlapping government, private and semi-private systems that made care both inefficient and expensive. Obamacare simply left all those inefficiencies in place, and added a bunch of new ones, with subsidies to make the whole package go down smoothly with the voting public.

In those overlaps, those inefficiencies, there are a lot of arbitrage opportunities for both consumers and health care businesses. Providers will do their best to shift their patients to whatever program offers the highest reimbursement, since insurers are no longer legally allowed to decline their business. And consumers will do their best to force insurers to bear the risk without paying for it in the form of premiums — by, for example, using the special enrollment period to buy insurance, or buy better insurance, in the event of an expensive illness.

Individually, this is perfectly rational. At the system level, it is, of course, insane and utterly unsustainable. But just as people who ask silly questions should expect silly answers, people who build an insane system should be fully prepared for the madness that inevitably follows.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Questions about Obamacare and reimbursement? Physician Credentialing and Revalidation ? or other changes in Medicare, Commercial Insurance, and Medicaid billing, credentialing and payments? Call the Firm Services at 512-243-6844 or [email protected]